Meykhana is a traditional, patriarchal and to some extent underground genre of Baku spoken-word art – a local mix of chanson and rap. As a rule, meykhana is comprised of the most complex style of Eastern poetry, called

Aruz

, in the form of a freestyle verbal face-off.

Since the Middle Ages and in Baku in particular, there have existed taverns and pubs where one could drink a glass of wine, smoke from a hookah, listen to music or ashiqs and play the games in popularity at the time. Among those who frequented these establishments were famous poets, musicians and dervishes of the time. Here they would read their compositions in a sing-song voice and tap out a rhythym to acompany their address.

The distinguishing trait of Baku meykhana was the poetic competitions between a tavern’s patrons. Couplets were voiced to the rhythmic accompaniment of a

daf

– a large Persian frame drum. One of the participants would provide a topic, after which there began an improvisational, comedic and satirical competition, in some ways reminiscent of Russian

chastushki

– humorous folk song.

A meykhana master, called a meykhanachi, is a quick-witted poet, ready to compose couplets on the spot to fit a given rhythm. An individual loses when they are unable to answer their opponent in time.

Swearing, demeaning or ridiculing an opponent – all this is acceptable in a meykhana competition. Only by having a sharp tongue and being able to effectively insult an opponent is it possible to get a reaction from the audience and onlookers. Because of this, opponents usually don’t take offense to even the rudest insults and don’t hold a grudge against one another.

From the Tavern to the People…

Religious leadership regularly banned meykhana. Taverns would close and open quickly depending on the political situation in the country. But poetry competitions gained such popularity that competitions referred to as meykhana began to be held outside the taverns as well, at celebrations and weddings. Some individuals began to be recognized by the people as meykhana professionals and were invited to weddings, for a price.

This style, a synthesis of poetry and music, was particularly beloved in villages around Baku, where over time people began to call for meykhana competitions at weddings and feasts. Now meykhana is called for and listened to at weddings in many regions.

Classic Meykhana Performers

The image of the classic meykhanachi is also noteworthy. As a rule, a classical meykhanachi was not a friend of the law, may or may not have a criminal record and was a fan of narcotic substances. According to other unstated rules, he was generally uneducated, lived outside the law, smoked and wore a mustache. He is called to weddings by enthusiasts of this art form and his personal fans. When this takes place, women should not be in the room, and usually remain in the courtyard under the wedding tent.

After all, the locale where a meykhanachi performs his art is, as a rule, wrapped in smoke from cigarettes and recreational narcotics. In the center, the masters compete in a game of words, and around them onlookers enjoy the spectacle. Despite the fact that there is also music in meykhana, this is first and foremost a poetic art. The music in meykhana plays a secondary role and is needed primarily to give a tempo for the poetry.

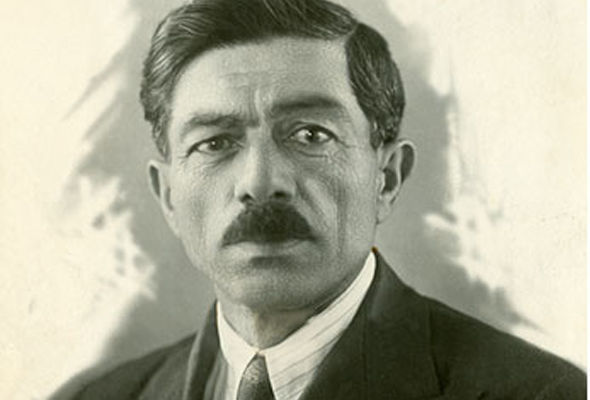

Since the time of its appearance, meykhana has always been an art outside the law, a unique bastion of the people. It has never been a genre beloved of those in power. Even in the Soviet period, meykhana performers might indulge in critique of the government. The most popular in the country was Aliagha Vahid – a dissident of the Soviet period. In 1991 the film

Ghazelkhan

was made about the life and works of Vahid.

Meykhana and Show Business

In 2001 the Azerbaijani TV channel ANS decided to organize a battle of meykhana performers and created a corresponding TV show in which viewers could vote by SMS. This set the groundwork for a new stage in development of meykhana and marked the beginning of its transition to show business. Meykhana performers came out of the shadows and were transformed into full-fledged participants in local show business.

They began to participate in TV shows as guests or even experts on various topics. It was no longer disgraceful for them to appear before the camera alongside representatives of sexual minorities whom they had previously denigrated in their texts. And in recent years, female meykhana performers have begun to appear on the screen as well, which was unimaginable in the 90s.

Women in Meykhana

Many in Azerbaijan know Samira Yusifqizi as meykhanachi Samira. She is the first woman who dared to compete with men in a televised meykhana duel. Since that time she has become serious about practicing this art form, leaving her main profession as a singer. Samira tells about the peculiarities and difficulties of her trailblazing act.

“Really, I had never had a particular, burning desire to become a meykhanachi, because I am a singer by profession. But since childhood I could compose lines instantaneously. I first tried my hand at meykhana in 1994, and I managed it. But I didn’t go public with this because there was a very complicated attitude towards female meykhanachi. Only recently did it happen that I and another meykhanachi –

Oqtay Kyamil

tried to do a duet, and it seems to have come off well. I became a sort of pioneer in this respect.”

Samira says that, though she does not take others’ opinions seriously in this matter, all the same it is sometimes difficult even now to be practically the only female meykhanachi in the public eye.

“

Imagine, you enter a room where there are sitting 500, 200, even just 100 men, and you need to go up against these masters of the spoken word! Someone will say, “Your place is in the kitchen, this isn’t women’s business”, while others, quite the opposite, praise me for bravery. It’s difficult. But what can you do, everything new is difficult”.

And indeed, male meykhanachi are not very happy about the fact that women are laying claim to their masculine, patriarchal rap. Samira admits that her male colleagues don’t particularly respect her and that she often faces discrimination.

“Many of my colleagues of the opposite sex are jealous of my success, try in whatever way possible to make me stumble, don’t want to accept me as a full-fledged meykhanachi, put a stick in the spokes”.

But the sole woman in meykhana thus far knows her weak and strong sides and does not despair.

“

I understand that my skill in composing meykhana can’t compare with their skills. Because they are constantly perfecting their craft. They don’t have the problems I do. They gather more often in tea houses or other places, compete, sharpen their skills. I am denied this opportunity. Nobody wants to compete against me. But I nevertheless try to also meet all the requirements of a good meykhanachi. And thank God, I still haven’t lost.”

How did a woman come to be a meykhanachi anyhow? After all, one might say that not one parent, not one family member will accept that a girl, a woman from among their kin, wants to become a meykhanachi. After all, this means that she will be a guest in smoky halls stinking of alcohol where competitions take place with unmentionable words.

But Samira lucked out.

“Even among relatives, most were opposed to the fact that I began to compose meykhana. But my family is my mother, daughter and son. And they had a positive opinion of my initiative. True, my son protested at first, but later he agreed, saying, “And why not. After all, someone needs to start this!” Clearly, I was fated to become the first woman meykhanachi. And everyone else’s opinion is not so important for me”.

Samira believes that she is fairly successful in her activities. After all, she managed to make it so that women and children have begun to love meykhana, as well. She managed to break the stereotype that meykhana is something masculine.

“I sometimes think about the fact that it would be good if other women and girls also got involved and would also begin to take up meykhana. After all, I am currently alone on the stage, among men. But, on the other hand, I’ve lived through so many difficulties on this path, heard so many awful words and stories about me, that I wouldn’t want for someone else to go through this.

But I am nevertheless thankful to meykhana. If not for meykhana, I would likely have been a mediocre singer, known only in a narrow circle. And this way the entire country knows me”.

Samira even agreed to perform a couple of couplets for us in Russian on the spur of the moment. In doing so, she waited for the woman passing by to move into the distance. Even after everything, she is uncomfortable…

The second woman who dared to make an appearance in the meykhana ring was Zarina. But Zarina didn’t compose meykhana, she sung it, which doesn’t match the format of this art form, however she did become very famous as a result.

Unfortunately we didn’t manage to speak with Zarina.

So far only an insignificant part of the male meykhanachi agree to have performers of the other sex join them. To a large degree, this is because of mentality.

Jahankesh Balakhanili, a young meykhanachi, is also opposed to women participating in meykhana. He believes that these arenas are not for women: after all, there is swearing there, smoking and a generally masculine atmosphere.

“A woman is a mother, a sister. How can one imagine her in such vulgar surroundings? And we too feel awkward when a woman is sitting in the room. After all, we are Azerbaijani men all the same, it’s understood you don’t swear around women or act “indecently”. And also the gesticulation in meykhana is unbecoming of frail women. And this is what meykhana consists of – gestures, atmosphere, sometimes swearing. This means that women should not be there”.

Praise for the Government is the Way to Honor

The show-business atmosphere has had its influence on the fate of meykhana.

Meykhana practitioners – the free-minded poets of the past – no longer permit themselves critical lines directed at those in power. Quite the opposite, many have begun to sing the praises of power. For example, the Rustamov brothers, who gained sudden popularity with their freestyle “Who the hell are you, hey, see ya’ later…” Later this song found its way to the big screen when they shot a clip praising the elder and younger Aliyevs.

In 2006, the president of Azerbaijan, Ilham Aliyev, personally awarded the elderly meykhanachi Agaselim Childagh the Shohrat Order (Order of Glory), one of the highest honors of the republic.

Many meykhanachi regarded this as an invitation to be loyal. Orders, apartments, titles, television performances: all this became a coveted dream for many representatives of this art.

In this way, when meykhana was an underground art form, its audience consisted primarily of the criminal and nearly-criminal community, who lived according to unwritten codes. In a word, a community that didn’t love those in power. When the path to a broader audience opened via television – which is fully controlled by the government – the composition of the audience and the interests of clients changed.

This laid the groundwork for changes to the essence of meykhana. It lost its archetypal form, its essence and its specific form. From a bastion of the people, from an art of freedom and dissent, it was transformed in some sense into a mediocre synthesis of poetry and rhythm.

***

Authors

Günel Mövlud,

Aziz Kerimov,

Haji Hajiyev