For more than a decade, the owners of SerbAz, an offshore company at the heart of the largest labor exploitation case in modern Europe, remained unknown.

Between 2006 and 2009, the company brought over 700 workers from the Balkans to build or renovate some of the most prominent buildings in Baku, the capital of Azerbaijan. These included a grand event space called the

Buta Palace

and a massive

exposition center

, both of which continue to be used for important state functions. Some of the projects were funded by the Ministry of Youth and Sports.

But the foreign workers who labored on these sites were treated as little more than modern slaves. They lived in cramped conditions, with little food, and worked grueling, 12-hour days. Their passports were confiscated and their wages withheld. Some were beaten, and at least two died.

When their case was discovered, the men were paid a fraction of what they were owed and sent home. The Azerbaijani government ignored those who called for accountability and blamed the company’s Balkan managers for the abuses. The police never pressed charges, a civil suit against SerbAz was swiftly dismissed, and the company’s owners remained a mystery.

The workers, their lawyers, and human rights organizations have long suspected that SerbAz was being protected by the authorities because its work benefitted well-connected insiders. But there has never been any proof.

This story refers to Rahimova’s company by its

public brand name, ItalDizain

. It is sometimes referred to in documents as “Italdizayn,” and two companies using that name — “Italdizayn CJSC” and “Italdizayn Group LLC (ID Group LLC)” — are registered in Azerbaijan.

Now, a years-long investigation by OCCRP reveals that SerbAz’s powerful backer was none other than Azad Rahimov, the Minister of Youth and Sports himself. There is strong evidence that, in hiring SerbAz, the minister was awarding contracts to his wife’s company, using public money to benefit his own family.

SerbAz appears to be a subsidiary of a major luxury importer called ItalDizain, a company owned jointly by Rahimov’s wife, Zulfiya Rahimova, and a man who appears to be his associate. Before entering politics, the minister himself was the director of ItalDizain.

Zulfiya Rahimova has never been publicly announced as Azad Rahimov’s wife, but they are officially registered at the same Baku address.

Rahimov was a political newcomer when he was appointed Youth and Sports Minister by President Ilham Aliyev in early 2006. A

U.S. Embassy cable sent

just a few days later describes Rahimov as “a close contact of the President and his wife.”

Since then, he has presided over a series of grand projects led by the ministry, which plays a key role in the Azerbaijani regime’s efforts to present a modern face to the world.

Most of the SerbAz workers were freed and left Azerbaijan in the fall of 2009 after their plight was made public. They are still waiting for their claims to be legally recognized. Meanwhile, Rahimov’s ministry continued to make payments of millions of dollars to SerbAz well into 2010.

Preferred Contractor

Azad Rahimov’s first chance to make a big splash came not long after his appointment as Youth and Sports Minister. In late 2006, it was announced that the 2007 European Rhythmic Gymnastics Championship would be held in Azerbaijan the following summer.

The event was of particular importance to Mehriban Aliyeva, Azerbaijan’s first lady and the president of the country’s official gymnastics federation.

But there was a problem. The proposed venue, a major sports complex named after the late former president Heydar Aliyev, whose son now rules the country, was in need of refurbishment.

Due to the urgency of the project, Rahimov later explained, there was no time to go through the normal bidding procedure. Instead, after receiving the required approval from another government agency, his ministry signed a 4.6 million manat ($5.3 million) contract with SerbAz.

Asked later to justify his rationale for selecting the company, the minister explained that the facility had “various configurations and complicated architecture” and that its refurbishment would require “state-of-the-art materials” manufactured abroad. For that reason, he needed to find an operator with “wide experience in this area.”

Not only did SerbAz lack any experience — it didn’t even exist when the contract was signed in March 2007. According to corporate records obtained by OCCRP, SerbAz was incorporated in Azerbaijan about a week later. Moreover, local media reported that the company had already begun work on the complex the year before it was formally selected to do the job.

The opening ceremony of the 23rd European Rhythmic Gymnastics Championship was held in the building on June 29, 2007. Spectators and athletes were greeted by President Ilham Aliyev. His wife, Mehriban, also spoke, perhaps already envisioning the new facility in use for her own projects.

President Ilham Aliyev’s wife Mehriban, who has served stints as a member of parliament and vice president, has long had an interest in gymnastics. She was elected president of Azerbaijan’s gymnastics federation in 2002, and

her official biography

describes her as an “accomplished coordinator” in the sport with “growing prestige on the international arena.”

After its renovation by SerbAz, the Heydar Aliyev Sports and Exhibition Complex became the home of Azerbaijani gymnastics, hosting a number of major international tournaments organized on Mehriban Aliyeva’s watch.

It was also the home of the country’s gymnastics federation until a company linked to the Aliyev family was awarded a government contract to build a still newer facility.

After completing the initial renovation, SerbAz received another ministry contract worth almost 600,000 manat ($700,000) to perform additional work on the center. But this was just the beginning.

Between 2007 and 2009, the company’s foreign laborers worked on at least six other projects in Azerbaijan. At least two of these were also financed by the ministry: A 17-million-manat ($20.9 million) restoration of the “Palace of Happiness” and the construction of a 32-million-manat ($38.8 million) Olympic rowing center. SerbAz’s other projects included the Buta Palace, the Baku Expo exhibition center, and 28 Mall, a well-known upscale shopping venue now owned by the Aliyev family.

The Palace of Happiness, a neo-Gothic mansion in the heart of Baku, is one of the city’s most noteworthy historical buildings.

It was built in the early 20th century by a local oil tycoon as a gift to his wife, who had admired a similar French building on one of the couple’s trips to Europe. During the Soviet period, it was renamed the “Palace of Happiness” and used as a venue for wedding ceremonies, a function it retains today.

In Rahimov’s letter to prosecutors explaining why SerbAz had been selected for the building’s restoration, he said the company “specializes in the restoration of historical architectural monuments.”

In reality, SerbAz had been incorporated just months earlier, and most of the workers it employed were simple laborers with no specialized experience. An RFE/RL story about the project

quoted a local architect

who dismissed SerbAz as “unprofessional” and “not a restorer.”

An Offshore Secret Comes Out

The links in this section lead to the corporate records of the relevant companies.

It has taken years to link Azad Rahimov to SerbAz, because the company’s ownership information is hidden in secretive jurisdictions thousands of miles from Azerbaijan. An Azerbaijani migrants’ rights organization, a Serbian human rights group, and Bosnian prosecutors have all failed to pierce the company’s opaque corporate structure.

In fact, SerbAz was actually registered as two different companies in different jurisdictions. In Azerbaijan, the company operates under the name

SerbAz Design and Construction

. It is owned by a firm called Acora Business, whose true owners cannot be determined because it is registered in the offshore jurisdiction of Anguilla. This is the “SerbAz” that signed contracts and received payments from the ministry.

The other SerbAz is registered in the Netherlands as

SerbAz Property

under a limited partnership, a corporate structure that allows absolute anonymity.

Both of these corporate paper trails were dead ends, but OCCRP reporters found another clue. According to a tip from an insider, another Azerbaijani company, Creacon Construction, took over the building work from SerbAz after the workers were discovered and returned home.

In 2012, Azerbaijan restricted access to corporate information, making company ownership structures a secret.

But before the company registry was taken down, Azerbaijani journalists managed to scrape part of the database.

The records show

that one of Creacon’s two shareholders was

ItalDizain Group

.

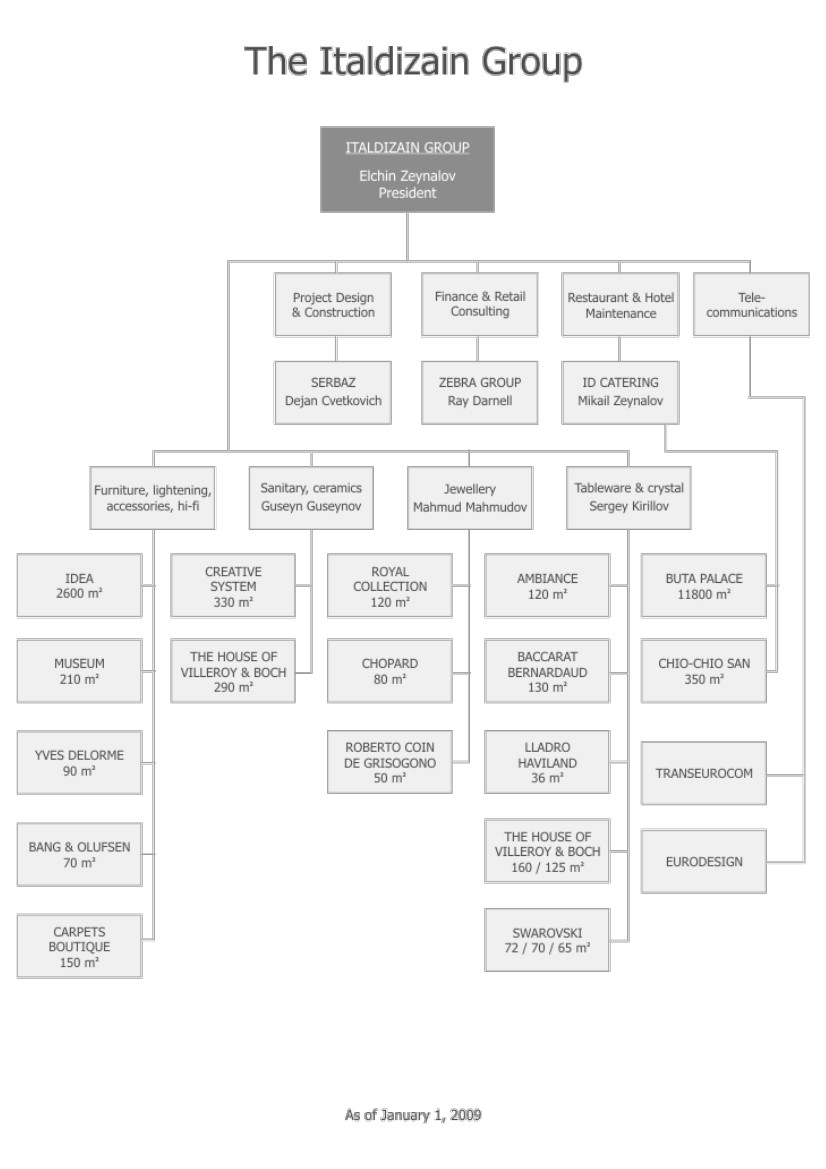

ItalDizain is well-known in Azerbaijan as an importer of luxury brands. It has also grown to become a major holding company that includes telecommunications, real estate, and upscale boutiques that sell everything from Cartier watches to Baccarat tableware.

A lucky break helped reporters complete the connection back to SerbAz. The Internet Archive, a non-profit library of millions of websites, had preserved earlier versions of ItalDizain’s site that contained a chart of its corporate structure showing SerbAz as its subsidiary as of January 2009, the same year the SerbAz workers’ brutal treatment was discovered.

There is other evidence SerbAz is a subsidiary of ItalDizain Group. For example, employment advertisements at the time describe the company as a subsidiary. In the "About Us" section of ItalDizain’s website, SerbAz is also identified as a subsidiary. Finally, sources confirmed the relationship.

Having established that ItalDizain was the ultimate beneficiary of the workers’ labor, reporters set out to learn who was behind it. Here, once again, the

scraped corporate records showed

the way.

They indicated that the luxury conglomerate is wholly owned by a Luxembourg company called Argulux. Argulux, in turn,

is owned by Zulfiya Rahimova

, the wife of Youth and Sports Minister Azad Rahimov, and Elchin Zeynalov, who appears to be his associate.

RAHIMOV AND ITALDIZAIN

There is evidence that Rahimov’s connection to ItalDizain goes beyond his wife’s ownership of the company.

ItalDiazain was incorporated in Baku in 1996. Between 1998 and his appointment to the Ministry in 2006, Rahimov was its director. The company’s shareholders are unknown, but a

leaked U.S. diplomatic cable

from 2006 describes him as the company’s co-owner.

Since January 2009, ItalDizain has operated under a new Azerbaijani corporate entity, ID Group. This is the company traced by reporters and co-owned by Rahimov’s wife and his associate, Elchin Zeynalov.

What Did the Azerbaijanis Know?

The connection of Rahimova, Zeynalov or any other senior Azerbaijani to SerbAz’s abuses has never before been brought to light. When the workers were discovered, the Azerbaijani government blamed their treatment on the Balkan men who managed SerbAz, interacted with the workers, and had presented themselves as the company’s owners.

As the workers’ experience shows, these men from their own part of the world really were in charge of their day-to-day mistreatment. The only criminal trial resulting from the case led to four convictions of Bosnian SerbAz employees on human trafficking charges.

Bosnian prosecutors later indicted 13 SerbAz representatives — the men who had recruited the workers in their home countries and ruled their lives in Baku — for human trafficking. Late last year, four of the indicted men admitted their guilt and one was sentenced to a year and nine months in prison. The others, including the Vučenović brothers, were found not guilty. The prosecutor has appealed.

But the trail of accountability ended there, partly because no serious investigation was ever undertaken in Azerbaijan, creating the impression that SerbAz was a rogue foreign contractor for which the government bore no responsibility.

But a raft of additional evidence, including photographs taken at the time, statements by multiple workers, and information from insiders about closed-door meetings, shows that powerful Azerbaijanis not only owned the company, but were also heavily involved in its operations.

One of the Azerbaijani men involved was known to the workers only as Samir. They identified him as one of the men who met them at the airport and confiscated their passports. They also describe him as one of their main abusers. Workers told reporters that the short, muscular man, whom they called “The Butcher,” openly carried a gun and often acted cruelly and violently. Once he beat a worker so brutally that another SerbAz employee had to intervene to stop him from killing the man.

One Azerbaijani man, whom the workers called “The Colonel” and understood to be a liaison between SerbAz and the ministry, was responsible for controlling their movement. Before the workers were finally deported, he forced them to sign statements that they had not been mistreated and had been paid in full. He then accompanied them to the airport and returned their passports, confiscated by SerbAz months earlier. According to the workers, he was in a position to “make a phone call” and resolve visa problems for those who were questioned by border officials on their way out.

Another key figure was Elchin Zeynalov, whom the workers understood to be a representative of the Youth and Sports Ministry.

In fact, Zeynalov was not formally a government official. But he is a key associate of Rahimov, having replaced him as the head of SerbAz’s mother company, ItalDizain, when Rahimov left the company to head the ministry in 2006. Zeynalov is also the company’s beneficial co-owner, along with Rahimov’s wife Zulfiya.

Two photographs obtained by OCCRP show him visiting the Buta Palace, one of SerbAz’s main construction sites, accompanied by two of the company’s Bosnian managers.

Rahimov also visited the sites to check on their progress, sometimes accompanied by President Ilham Aliyev. In an interview, one of the workers recalled being ordered to say “khorosho!” — the Russian word for “good” — if the visiting president asked how they were doing. The workers threatened to tell the president “nyet khorosho” instead. They were given the day off when Aliyev visited— the only such break they ever received.

When a Bosnian consul met with Rahimov to discuss the workers’ case after the affair became public in October 2009, the minister presented himself as a concerned official whose ministry had already investigated SerbAz’s abuses and introduced a new government “coordinator” to set things right. But a report about the meeting, used as evidence in the Bosnian criminal case, shows that Rahimov told the consul he was personally aware of SerbAz’s abuses as early as May 2009, when he ordered an investigation of them. He described the confiscation of the workers’ passports as a violation of their “basic human rights.” The “coordinator” he appointed, according to the minutes, was a man named “Elchin” — perhaps a reference to Elchin Zeynalov, Rahimov’s long-time associate and in fact one of SerbAz’s ultimate owners. There is no mention that Rahimov told the Bosnian consul his wife and Elchin Zeylanov owned the company.

Though Rahimov claimed to be unhappy with SerbAz’s performance, and said that his staff had discovered “irregularities” in its work, his ministry awarded the company a new multi-million-dollar contract in October, the same month the workers were discovered and the work halted.

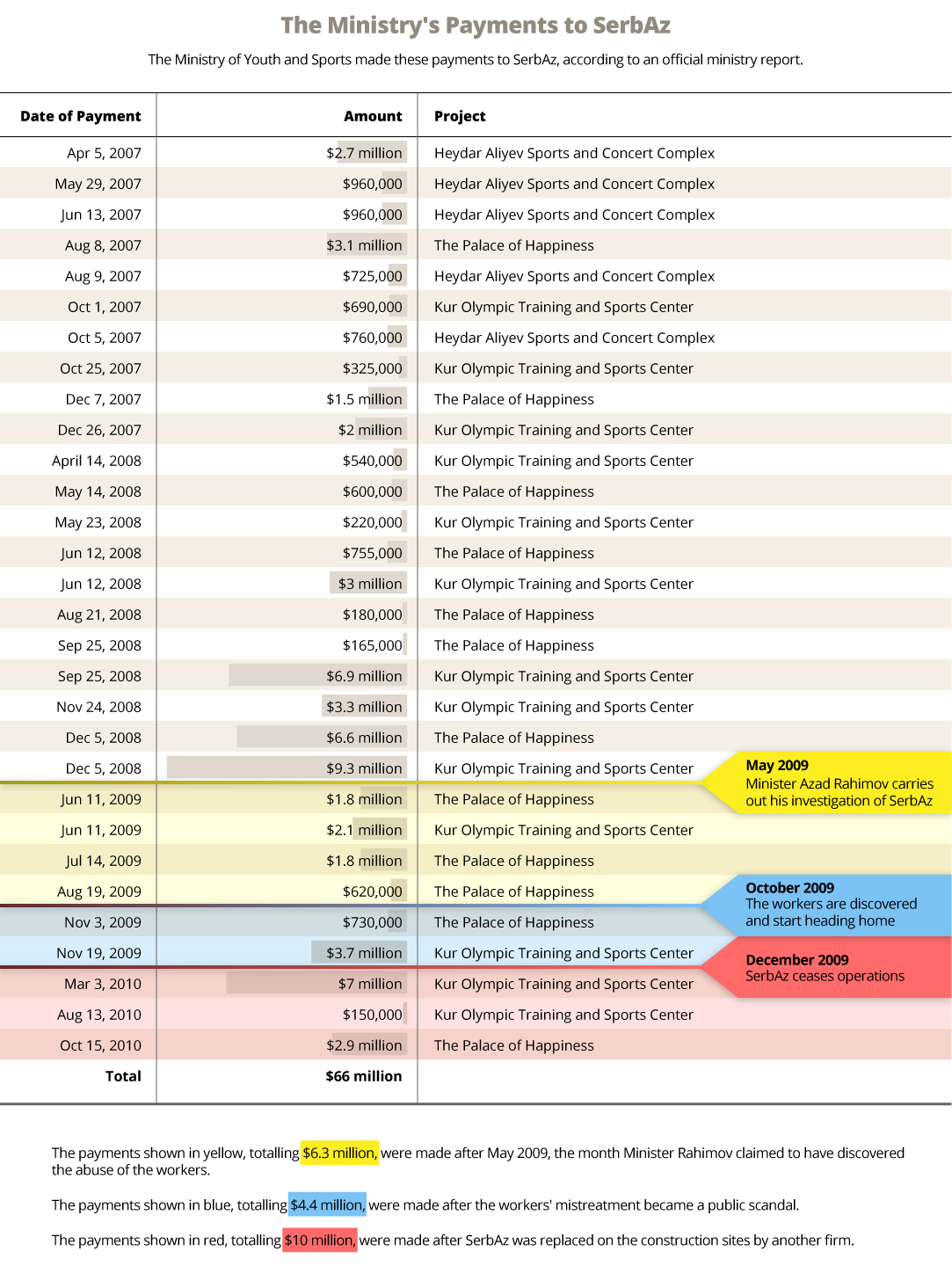

The ministry also made payments totalling $6.3 million to SerbAz between May and October. The workers themselves received nothing during that time, raising the question of what happened to this money. According to a SerbAz insider’s account, the company dealt in cash, and who exactly controlled its finances is unknown (see box).

The inner workings of SerbAz are still largely a mystery because the company made payments in cash and intimidated those who would challenge it.

Even its corporate documents are no longer available — having been taken by its mother company, SerbAz has claimed — making it much harder to trace its activities and ownership.

A SerbAz manager who spoke with reporters on condition of anonymity said that payments from the government arrived at the company’s main office in suitcases of sequentially numbered bills. Suppliers of cement or other materials were paid directly from this cash stockpile, without proper accounting procedures. When electronic money transfers did take place, the payments were often made to offshore accounts. Some shipments, including expensive marble imported from Spain, were paid for with SerbAz money and then driven away, presumably to a different project, he said.

Moreover, in text messages later intercepted by Bosnian investigators, a Bosnian SerbAz manager wrote to his former boss and advised him to admit, probably to Bosnian prosecutors, that Zeynalov, along with the company’s Serbian director, were responsible for the disappearing money. The director and Zeynalov “took over the company in the fall of 2009,” he wrote, “stole money from the company, didn’t pay workers, and did whatever they wanted.”

The Youth and Sports Ministry continued to make payments to SerbAz after the workers’ abuse was made public, sending another $4.4 million to the company in November 2009. It paid the company another $10 million the following year, long after its construction projects had been taken over by another company.

Rahimov, Rahimova, and Zeynalov didn’t respond to requests for comment for this story.