At age 36, Maharram Zeynalov writes poorly and reads slowly. It was just a few years ago that the journalist found out the reason why he never learned to read fluently. It was by accident that his psychiatrist friend told him.

“In school, my reading and writing notes were always the worst”, Maharram recalls. “I had top notes in my other classes, but in Russian I’d fail. My teacher was puzzled, and would ask, ‘Why is he so illiterate?’”

At the time, no one tried to find out why Maharram had these problems at school, their cause or how they could be tackled. If it were not for his psychiatrist friend, Maharram would probably never have learned that his problem has a name: Dyslexia.

“When I told him it takes me a week to read one book and I suffer when I am reading, he said me ‘Dude, you have dyslexia", Maharram says. “It was then that I had a flashback, I started recalling that I read slowly in first and second grades."

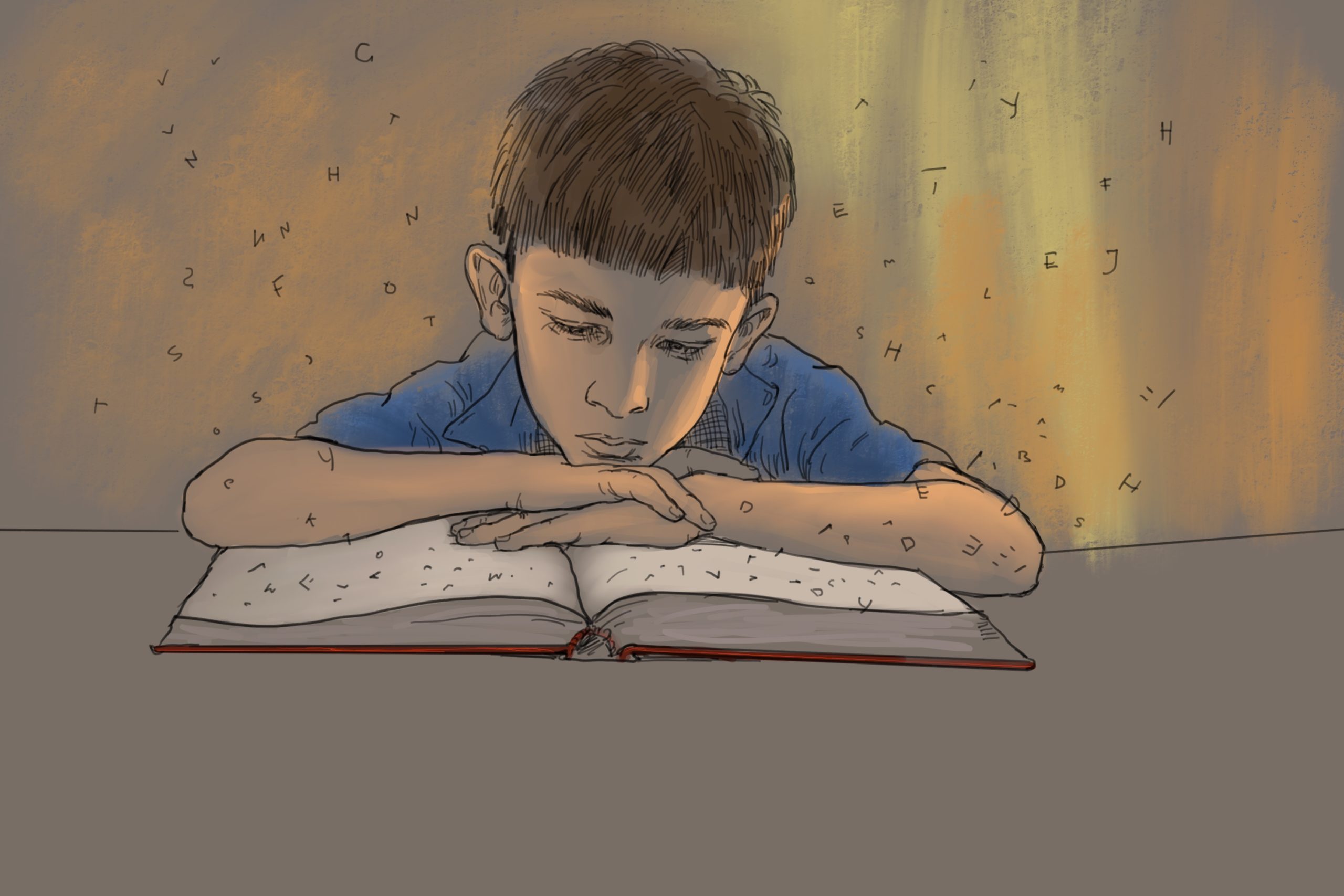

Dyslexia is written speech disorder characterized by difficulty mastering reading. A person with dyslexia has difficulty reading and writing, despite having a level of intellectual and speech development that should sufficient to do so.

How does one identify dyslexia?

“Parents often find out that their child has dyslexia when the child is six or seven years old, I mean, probably in first or second grade in secondary school, when the child is learning to write and read," Lola Preobrazhenskaya tells Meydan TV. She is a children's psychologist, a special education teacher, and the director of the children's game and psychological support center "White Rabbit" in Prague.

However, she says, by monitoring one’s child at an even earlier age, parents can identify whether the child has dyslexia as early as age two or three.

"If your child does not start speaking by age three, that is a red flag. One has to sound the alarm even at age two and a half and take classes with a speech therapist to prevent further manifestations of dyslexia," the children's psychologist explains. "Then, we pay attention to whether the child is able to distinguish sounds in words. Does the child understand what sound or letter the word starts with? These kinds of neuropsychological exercises can also help. We take and connect the thumb with all other fingers on the hand and check that the child can repeat the exercise after us. Besides, these kinds of children are often unable to remember sequences. For example, days, weeks, and months. This can be checked in small children, too."

Lola Preobrazhenskaya also points out that more often than not, people have a genetic predisposition for dyslexia.

"Scientists have long been saying that dyslexia is hereditary," the psychologist says. "There is the theory that dyslexia is more common in men than in women, and it has something do with testosterone."

Maharram accepts the idea that dyslexia could be hereditary in his family, too.

"I think that my father had dyslexia, too, because he read slowly and was a rather illiterate person, but it is just that nobody called it dyslexia back then. People called such people lazy or absent-minded," he says. "But my brother is doing even worse than me in terms of dyslexia. He still reads very poorly. My son is eight, he reads better than does my brother, who is 32 years old. My brother still reads letter for lettes, and he just cannot write, he is terrible at writing."

People do not talk about dyslexia in Azerbaijan nowadays, either. Many simply do not know what it is about.

"Our people also perceive dyslexia as laziness or absent-mindedness. When I, for example, tell my friends that I have dyslexia, their response is that I am simply absent-minded, there is no such problem and I made it up."

Study as torture

The web helped Yelena Danilova, back then a foreign language teacher, realize that her child had dyslexia. At present, Yelena is the director of the Social Dyslexia Center in Kazakhstan and a specialist in learning difficulties. She tells her story of identifying dyslexia and overcoming problems that it involves.

"When my daughter went to first grade, things seemed to be fine with her studies," Yelena says. "But as soon as in second grade, we realized that she started having problems reading. She was poor in reading and had problems writing and understanding texts or, for example, memorizing poems. We’d learn the poems by drawing pictures."

And as soon as third grade, the mother realized that it was "not just a problem of study, wrong schooling or anything else".

"She and I spent hours doing her homework. It was torture for both her and me. We’d be storming out of the room, both of us yelling and crying. It was actually a very serious psychological problem," Yelena recalls.

It was in school, however, that the girl encountered more serious psychological problems.

"When she started reading aloud, people around laughed and said things like, “Let’s not let Lera read today, otherwise she will take half an hour.” She would wake up in the morning and beg not to go school. When I asked her why, she said she was afraid of being laughed at at school. It was the start of third grade, when all children had learned to read fairly fluently. And for me as her mother it was like a knife being driven in my heart," Yelena says.

In parallel, Yelena’s daughter also starting having social problems. Due to the dyslexia, she began to isolate herself from her classmates and almost never talked to them.

Google to the rescue

Yelena contacted a speech therapist, but they did not find any problem with Lera.

And then Google came to Yelena's rescue. She did a bit of search on the web and realized her child might have dyslexia.

Yelena then decided to contact specialists.

"I started searching for what methods of correction there could be for this kind of a special child. Unfortunately, I found nothing," Yelena says. "We saw a psychologist – no results, we saw a speech therapist – no results, we took her to a speedreading course – no results there either. When Lera started doing the speedreading course, but she only improved by one word a minute after six months. They made a helpless gesture and said, “She is a good child, but we do not know what else to do."

In Moscow, Yelena's daughter was officially diagnosed with dyslexia. In Kazakhstan, she saw a specialist. Speech-language pathologists, social special education teachers and lately also neurologists and neuropsychologists deal with dyslexia problems.

"The thing that surprised me was that my child underwent complete change within six months," Yelena says, sharing her impressions. "I mean, she went through correction and just three months later her teachers started telling me that the child had begun listening to them. They tell me – what have you done to the kid, your child has become attentive."

Dyslexia is not a verdict

But the thing that Yelena was happy about more than about anything else back then was that her daughter was no longer bothered by her condition.

"Yes, she has dyslexia, she knows it, and she’s accepted it. It is something that makes her special. She does not read fast, she reads slowly and thoughtfully. She tells me, “I know now what my strengths and weaknesses are, and I will overcover my weaknesses with my strengths. She is very good at drawing comics, and she is quite happy with the way she is. And she says gladly that she has dyslexia."

Maharram Zeynalov is a journalist. Writing and reading is what he does for a living. However, Maharram says, becoming a journalist was the right choice for him as a person with dyslexia.

Because nobody dealt with Maharram's problem, he decided to take care of himself and accept his dyslexia as a challenge. "I very much love reading books but I read slowly and it causes me big problems. For this reason, I listen to books. I write very illiterately. But this is what I think – are you bad at language? Make it part of your work. You simply start treating it as a challenge. That is the best way to solve the problem," Maharram believes.

Yelena Danilova's daughter is now 12. As the mother of a person with dyslexia she has come a long way from identifying the problem to solving it. She advises parents to be more attentive to their children and not to ignore problems if they seem to arise. Dyslexia cannot be ‘cured’. But one can and should try and improve the life of a child who has this diagnosis.

"Don’t assume child will learn with time," Yelena recommends. "This is not just about learning skills. It affects the child's entire life, it affects absolutely everything – from their psychological condition to their social skills. I am not saying this will happen to all children, but at least 50 per cent of such children will experience socialization problems and psychological problems.

Produced with the support of the Russian Language News Exchange