From 25 November, the International Day for the Elimination of Violence against Women, to 10 December, Human Rights Day, the

16 Days of Activism against Gender-Based Violence Campaign

is a time to galvanize action to end violence against women and girls around the world. This year, the UNiTE Campaign will mark the 16 Days of Activism against Gender-Based Violence under the overarching theme, “

Leave No One Behind: End Violence against Women and Girls

”— reflecting the core principle of the transformative 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development.

As part of the 16 Days of Activism, Meydan TV is publishing an in-depth look at human trafficking in Azerbaijan. This is the second of four parts. Part one can be read

here

.

PART TWO

Coerced, Recruited

Only men and boys frequented the dimly lit Internet café in the town near Khayala’s village, some to play video games, others to look at pornography. With no publicly available Internet access appropriate for women and girls, Khayala asked to use her neighbor’s computer to search for job opportunities. Her neighbor, a young woman raised in Baku who married and moved to Khayala’s village, said she knew about a company in Baku that helps Azerbaijani women find work in Turkey and Dubai. She told Khayala that a babysitter, waitress, or housekeeper could make much more money abroad. The company in Baku would even provide Khayala with travel documents and an apartment. The neighbor encouraged her to go to the company.

Khayala’s neighbor represents a typical first line of contact in many trafficking operations. The United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees published a

working paper

on the trafficking of women in 2003. The report states that trafficked women are often approached by members of their own communities who have been paid by higher-level traffickers to lure women abroad with promises of jobs in the service sector. Another common recruitment tactic is using men to coerce young, single women with promises of marriage and a better life.

Arif Yunus, a human rights activist and former political prisoner targeted by the government of Azerbaijan for his social justice work, wrote a

report about human trafficking for the Migration Policy Centre

in 2013. According to his research, many women in Azerbaijan are recruited by someone they know, and “in most cases, the recruiters [are] other women: friends or neighbors.”

Khayala had never left the region before. She didn’t have luggage, so she packed her clothes in a thick plastic shopping bag. The cheap material had splintered around the edges, and the blue and red stripes had faded from years of use. The inside was ruddy from tomatoes and smelled of earth and onions. It was winter. She covered the bruises and ruptured blood vessels that splayed across her skin with layers of clothes and focused on the journey ahead. Late at night, Khayala left her husband sleeping and took her child to stay with her mother.

Many of those who are exploited, like Khayala, leave home determined to better their lives. Human trafficking is often inaccurately portrayed as something that occurs to naïve or helpless females. In reality, one expert says, both men and women are in danger because they lack awareness of trafficking.

“They don’t know what human trafficking is, how they can be victims,”

said Alovsat Aliyev in a Skype interview with Meydan TV. Aliyev, the former director of the Azerbaijan Migration Center Public Union, is seeking asylum in Germany for fear of persecution by the government of Azerbaijan for his work as a human rights advocate.

Arriving at the address in Baku that her neighbor provided, Khayala was greeted by a woman who introduced herself as the director of the employment services agency. The woman served Khayala tea and told her about the jobs available in Turkey. She took Khayala’s photo and told her that her passport and work visa would be ready in the morning. She would leave the next day for Istanbul. That evening, Khayala was housed in a cheap hotel on the outskirts of Baku with five other young Azerbaijani women from the regions. They were all surprised at how quickly they were being accommodated and were eager to get to work. The next day, a male employee of the agency accompanied the women to Istanbul from Heydar Aliyev International Airport in Baku, holding onto their travel documents “for safekeeping,” he explained.

Experts interviewed by Meydan TV agree that most Azerbaijani women who are trafficked come from western and southern Azerbaijan. The majority of women, like Khayala and the others with her, are flown from Baku to countries such as Turkey and the United Arab Emirates. Women from the south of Azerbaijan are often taken to Iran. Interviewees also described situations in which women are exploited domestically, forced to work as prostitutes in massage parlors and brothels, or as domestic servants for wealthy families in Baku.

According to a human rights researcher from Azerbaijan, the Nakhchivan Autonomous Republic – an exclave of Azerbaijan landlocked between Armenia, Iran, and Turkey – is a major transit point for trafficking to Turkey. He told Meydan TV in an informal interview that at the time of his research, traffickers were flying groups of women from Ganja to Nakhchivan via Azerbaijan Airlines. From there, they were taken by bus to Turkey.

A 2009 report funded by the Norwegian Helsinki Committee,

Azerbaijan’s Dark Island: Human Rights Violations in Nakhchivan

, describes the region as “the most repressive and authoritarian” part of Azerbaijan. When asked by Meydan TV about trafficking in Nakhchivan, Mehriban Zeynalova, Director of Clean World Public Union, stated that it is not a problem there. However, according to her

2005 repor

t, she interviewed 79 women who were trafficked to foreign countries from Nakhchivan and seven women who were sexually exploited within the territory. According to the report, “officials of all law enforcement bodies of Azerbaijan, such as border and custom services and police, take bribes from traffickers.” This explains how traffickers are able to travel with ease.

In Istanbul, Khayala and the other women were taken to a large, grimy apartment building surrounded by barbed wire in an unlit, poor neighborhood far from the city center. Each woman was taken to a different room. Once the women were separated, the man who had taken them from Baku severely beat Khayala, ripped off her clothes and took photographs. He told her that she owed him a debt for bringing her to Turkey, and that she could only repay him by working as a prostitute.

As Khayala’s story illustrates, traffickers use a variety of tactics to exercise control. A 2009 report by the

International Centre for Migration Policy Development

cites

“misinformation, manipulation, [and] lack of access to information and support networks”

among usual tactics. These are often used along with physical and/or sexual violence, confiscation of documents, nonpayment of wages, blackmail and threats.

A woman entered the room – the madam of the brothel – and explained that a special bank account would be opened for Khayala. The woman said that once Khayala made enough money to repay them for the travel documents and transportation, she could have her passport back and take the rest of her earnings. She lied.

The word “madam,” or alternatively “Mama Rosa,” is commonly used for a woman who takes a share of the earnings of sex workers under her control. In Khayala’s case, the madam was a trafficker profiting from forced prostitution. According to the

2014 Global Report on Trafficking in Persons

published by the United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime, “half of the traffickers in Eastern Europe and Central Asia are women.” The global average is lower – about 30 percent. Even those who work in the field are surprised by the number of women who are traffickers as it does not conform to commonly held beliefs about women. A male Azerbaijani human rights defender said during an interview with Meydan TV, “The fact that these types of crimes are being done by women is not believable.”

Women are active in trafficking, but experts in Azerbaijan say that they do not account for the majority of traffickers. The OSCE Special Representative and Coordinator for Combating Trafficking in Human Beings

expressed concern during her 2012 visit to Azerbaijan

that government figures that depict traffickers as largely female. She said it is a deliberate policy of high-level exploiters to use, or even force, some women into recruiting, which is more easily detected by law enforcement. The OSCE representative said that female recruiters are caught while the majority, mostly men, are not.

Men are also targeted by traffickers. An independent attorney in Azerbaijan who asked to remain anonymous said in an interview with Meydan TV that even though sexually exploited women are the largest trafficking demographic globally, men subjected to forced labor make up the majority of those trafficked in Azerbaijan. In 2015, however, the government of Azerbaijan officially recognized only nine labor victims. Alovsat Aliyev, former director of the Azerbaijan Migration Center, told Meydan TV that this reflects the government’s lack of interest in investigating labor trafficking because the government benefits from it.

According to investigations by the Organized Crime and Corruption Reporting Project (OCCRP) and RFE/RL, led by journalist and former political prisoner

Khadija Ismayilova

, both the extended families of President Ilham Aliyev and his wife, Mehriban Aliyeva (née Pashayeva), profit from construction projects through hidden ownership of several construction companies. This “empire of hidden wealth” was also revealed in the

The Panama Papers

.

One such company is Pasha-Holding, which is controlled by President Aliyev’s father-in-law, Arif Pashayev. The former director of the Azerbaijan Migration Center, Alovsat Aliyev, held a

press conference

in Baku on December 18, 2013 – International Migrants Day – to draw attention to the problem of forced labor in Azerbaijan. He named Pasha-Holding as one of the companies that use migrants as forced labor.

In an interview with Meydan TV, Alovsat Aliyev alleged that the

Flame Towers

, 28 May Mall, Buta Palace,

State Flag Square

, and the Kur Olympic Center were projects built by exploited workers. Turkish and Uzbek nationals were among the trafficked men who sought help from the Azerbaijan Migration Center.

The madam warned Khayala that if she disobeyed or tried to escape, she would be turned over to the Turkish authorities as an illegal immigrant and a prostitute. She claimed to have connections with high-level officials in Azerbaijan who could make Khayala disappear. The madam also threatened to post the nude photographs of Khayala on the Internet or send them to her husband and family. Terrified, humiliated, and convinced that there were no other options, Khayala obeyed.

According to reports on trafficking, shame discourages those who are being exploited from seeking help and also affects survivors of human trafficking when they return home. In an

interview conducted in Azerbaijan by the International Organization for Migration in 2008

, a woman from Ujar explained why she did not try to escape from traffickers in Dubai.

“After all, what was I going to do after that? How could I return home? What would I say to my parents?”

she stated.

Khayala remained in the brothel for six months. She was subjected to routine beatings, starvation, sleep deprivation, and psychological torment. The madam and her accomplices told Khayala she was worthless, that her family would never take her back. She was forced to have sex with an average of eight or nine clients per day. The men did not use condoms. When the traffickers realized that Khayala had become pregnant, they brought someone in to perform an abortion. Khayala bled for days. Her captors refused to provide medical care or allow her to go to a hospital.

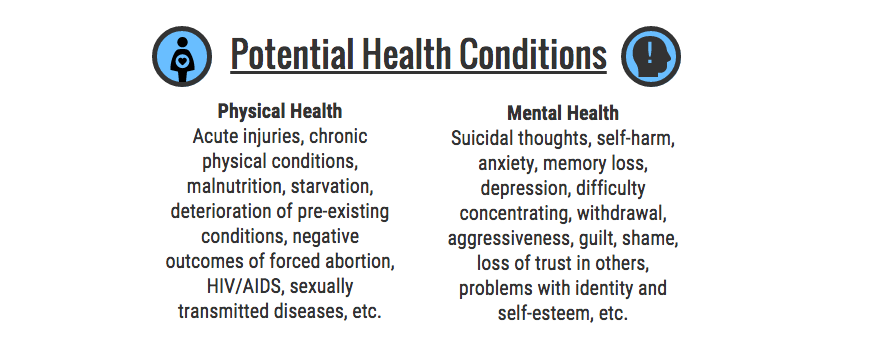

Like Khayala, many women who have been sexually exploited suffer greatly, both mentally and physically. A

report based on a two-year multi-country study by the London School of Hygiene & Tropical Medicine

details health conditions that result from physical and mental abuse.

Unable to perform sexually due to complications from the abortion performed by a nonprofessional, Khayala became less valuable to her captors. They stopped feeding her and left her unattended, assuming she was too weak and dejected to attempt to leave. One night when she was left alone, Khayala ran from the building. She took only a blanket, which she threw atop the fence to protect her from the barbed wire. She found her way to a police station. After some time at a detention center, she was deported to Azerbaijan as an illegal alien and prostitute.

According to the

previously mentioned 2005 report by Mehriban Zeynalova and Clean World Public Union

, Khayala’s escape and subsequent deportation is the way that most women are able to break free from forced prostitution abroad and return to Azerbaijan. Some are discovered during police raids, some are inexplicably let go by their traffickers and others are sold repeatedly until they disappear forever.