One of the peculiar traits of President Donald Trump is that he’s fulfilling his campaign promises.

One of them was his intent to annul the nuclear deal with Iran, regarding which Trump stated that, when the deal was concluded, the USA was seen as ‘very stupid’, and that Tehran got more out of the deal than Washington. Perhaps he believes that Iran, which has opened its nuclear facilities to IAEA inspectors, is keeping secret some sort of important elements of the program.

Iran was, to a large extent, forced to make an agreement by sanctions which made it more difficult to attract foreign investment and technology. But despite significant detriment, the Iranian leadership continued its uranium enrichment program and continued testing its primary, Shahab-series missiles, since it considers the presence of nuclear and missile weapons to be a means of weakening political and military pressure.

Experts believe that the thaw in American-Iranian relations since the conclusion of the Joint Comprehensive Plan of Action has come to an end. But it’s not such a simple thing to annul the agreement. The administration still needs to formulate a policy for relations with Iran, consultations will be needed with other participants to the agreement. And unilaterally breaking off the deal would inherently undermine trust towards the USA. And indeed, the European Union warned Trump against breaking the agreement.

After the nearly accidental discovery in 2002 that a uranium enrichment facility was being constructed in Natanz, in secret from the IAEA, Iran’s nuclear program took a central place in the USA’s foreign policy and became one of the problems for maintaining international nuclear nonproliferation. The Joint Comprehensive Action Plan between Iran and a group of states (Russia, the USA, the UK, France, the PRC, and Germany) as well as the European Union, was an attempt at resolving this problem. The parties agreed that Iran would give up developing nuclear weapons and provide IAEA inspectors access to its nuclear facilities. In exchange, the West would put an end to sanctions. But the problem was that the production of materials for atomic energy and production of materials for nuclear weapons requires an almost identical technological process.

The problem of the Iranian nuclear program influences many geopolitical alliances and forces many nations, particularly neighboring ones, to change their approach to regional politics. One such neighbor is Azerbaijan, from where the state of the Iranian economy is being lightly monitored. Previous to the Joint Comprehensive Action Plan, Azerbaijan was seen as a key component of the USA’s policy towards Iran. This presents Azerbaijan with the need for balance. It is actively developing a partnership with the USA in the areas of security and the fight against international terrorism, and sent troops to Iraq and Afghanistan. But it won’t allow its territory to be used for making military strikes on Iran. Clearly Azerbaijan and Iran’s relations in the near future will be complicated. Israel plays a definite role in this.

Since the scandal connected with the case of Mordechai Vanunu, the Israeli physicist who revealed information about Israel’s production of nuclear weapons at the Negev Nuclear Research Center, there has existed only one nuclear power in the Middle East – Israel – for which the appearance of a counterweight in the form of Iran presents a threat. These concerns have become a sources of tension between the USA and Israel, which is demanding decisive action from Washington. The USA is forced to bring to bear the weight of its authority in order to not allow an escalation of the conflict. Israel was offered modern arms to a sum of $10 billion, but the USA refused to supply it with special aerial bombs allowing for the elimination of underground targets.

As a partner of the USA and Israel, Azerbaijan is in a sensitive position, especially if we take into account Iran’s dissatisfaction with the strengthening of the military alliance and exchange of intelligence data between Israel and Azerbaijan. As recently as December of 2016, Iran expressed dissatisfaction with the visit to Baku of the Israeli Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu. In response, Baku stated that Iran cannot interfere in Azerbaijan’s internal affairs, noting that when the president of Iran visited Armenia, Azerbaijan didn’t make any sort of statements. Interestingly, the Armenian media didn’t hide its joy regarding Netanyahu’s visit to Baku, believing that strengthened relations between Israel and Azerbaijan might force Tehran to cut off cooperation with Azerbaijan in favor of Armenia. Though concerns were voiced that Israel might supply Azerbaijan with modern weaponry.

Turkey, the only Muslim country that is a member of NATO, didn’t express particular concerns regarding the Iranian nuclear program, clearly believing that the 70 American nuclear warheads deployed on its territory are enough of a deterrent. With such guarantees, it absolutely might believe that a nuclear Iran won’t pose a threat for it. But if Iran continues to develop its nuclear program, then it will turn out to be at least on a level with Turkey, whose nuclear program is at the earliest stages of development. Accordingly, at an unofficial level Ankara has a negative attitude towards Iran attaining nuclear status. This, in turn, might lead to even closer relations between Turkey and Israel, who Iran already suspects of exchanging intelligence data picked up by American radar in the Turkish province of Malatya and Israel’s Negev Desert, which moreover have similar technical characteristics.

Saudi Arabia and Iran have historically been in conflict with one another. The Ayatollah Khomeini believed that the House of Saud had not right to be custodians of the holy places. But of course, this isn’t just a matter of religion. Last year, after the sanctions were lifted, the Iranian economy showed five percent growth and might maintain this number in 2017; and indeed, Iran’s oil production reaching pre-sanction levels creates competition with Saudi oil. And Riyadh has already been enduring a major crisis since 2010, with a budget deficit of $100 billion. There are plans to reduce the state apparatus and wages for functionaries. The only budget not cut will be for military expenditures, which consisted $93-95 billion in 2017. Clearly the country’s government views military strength as a means for maintaining geopolitical weight in the region.

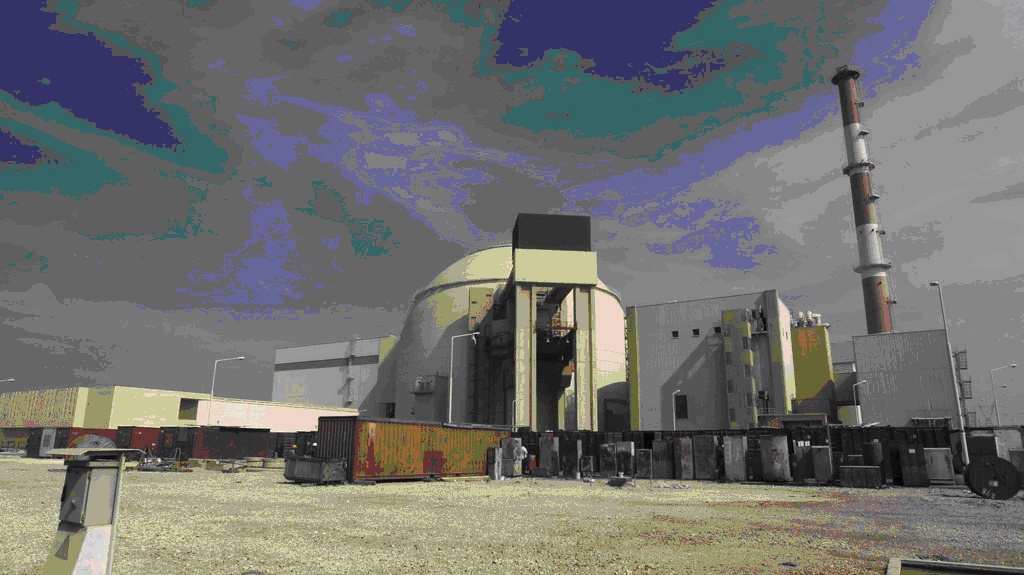

Despite the weight of this tangle of contradictions, the problem of the Iranian nuclear program must somehow be solved. Sanctions against Iran have already been in place for many years, and despite their serious negative effect on the Iranian economy, Tehran has changed almost nothing in its nuclear policy. In connection with this, the USA is trying to convince not so much the Iranian leadership as the country’s population of the inadvisability of the nuclear program in its present form. The primary arguments are that the cost of the Iranian nuclear program, from the point of view of missed investments and income from oil export, exceeds $100 billion; the construction of a nuclear power station in Bushehr took a total of about forty years, and the expenditures were around $11 billion, which makes this reactor one of the most expensive in the world, but it supplies only 2% of Iran’s energy needs, whereas 15% of the electric energy produced in the country is wasted because of technically outdated transmission lines. The nuclear power station in Bushehr is located on the juncture of three tectonic plates, which is dangerous from the point of view of its capacity for withstanding earthquakes. The objections listed here are expressed via policies of so-called ‘soft power’. But it’s unlikely that the Iranian leadership will cease implementing its nuclear program, which is a point of pride for the majority of the population.

The closer Iran is to creating nuclear weapons, the more often one hears discussions of using military force to prevent this. But experts believe that a military strike on Iran’s nuclear infrastructure, which would set back the program by four years, would significantly strengthen Tehran’s motivation to create nuclear weapons in hopes of staving off similar attacks in the future. Naturally, Iran will leave the Treaty on the Non-Proliferation of Nuclear Weapons and the IAEA and close access to data on its nuclear program. And indeed, it’s worth considering the consequences of such a blow for the environment of the entire Middle East. Moreover, Iran’s territory is not only desert, but also difficult-to-pass mountains and thick forests, which are comfortable locations for the development of guerilla movements. Expected countermeasures would be placing mines in the Strait of Hormuz and shipping lanes in the Persian Gulf, which would lead to a breakdown of up to 40% of the worldwide supply of oil. True, such a version wouldn’t be beneficial for Iran itself, which exports raw oil and gasoline, among other places, to Europe, which for the moment prefers to conduct mutually beneficial trade with Iran. And we cannot fail to take into account that as a countermeasure Iran will begin to sponsor the terrorist attacks of organizations such as Hamas, Hezbollah, or Ansar Allah. Moreover, an extremely negative reaction might be expected from the governments in Kabul, Baghdad, Islamabad, and other countries.

It’s more than doubtful that Russia will remain a non-participant in a military conflict around its sea-borders, and also in a country in which it has interests. Iran and Russia are historical rivals with common interests. For example: the wealth of the Caspian and influence in the South and North Caucasus. And on the oil market Russia and Iran are competitors. But today, Iran is an important market for Russia, including in the sphere of nuclear energy. Russia built the nuclear power station in Bushehr and is supplying fuel for the nuclear reactor there. The construction of another two nuclear reactors is planned, with the possibility of expanding this number to eight.

And since Russia sees Shiite Iran as a counterweight to hostile Sunni radicalism, it is the primary supplier for Iran of conventional weaponry and missiles, including C-300 missile systems and Antey-2500 SAM systems. But in the Kremlin, they can’t fail to understand that the appearance of an ‘Islamic bomb’ on the southern border would become a much more serious problem for Russia than the USA. Iran does not have the means for delivering a nuclear payload to the territory of the United States, and such a development isn’t expected in the near future. But Iranian missiles absolutely might reach Russian territory.

Clearly the USA is concerned not by the appearance in Iran of nuclear power stations, but the production of uranium by Iran for military purposes. If the USA annuls the nuclear deal, then Iran might renew its nuclear program in full, and without control. To what extent the USA is prepared to go in this question is so far unclear. In order to avoid an escalation of tensions, all interested countries must act in close coordination with one another. The main impediment along the path to this is the lack of confidence that these countries share common values and ideals. And for the moment, there’s a bill up for review by the US Congress “To authorize the use of the United States Armed Forces to achieve the goal of preventing Iran from obtaining nuclear weapons”.