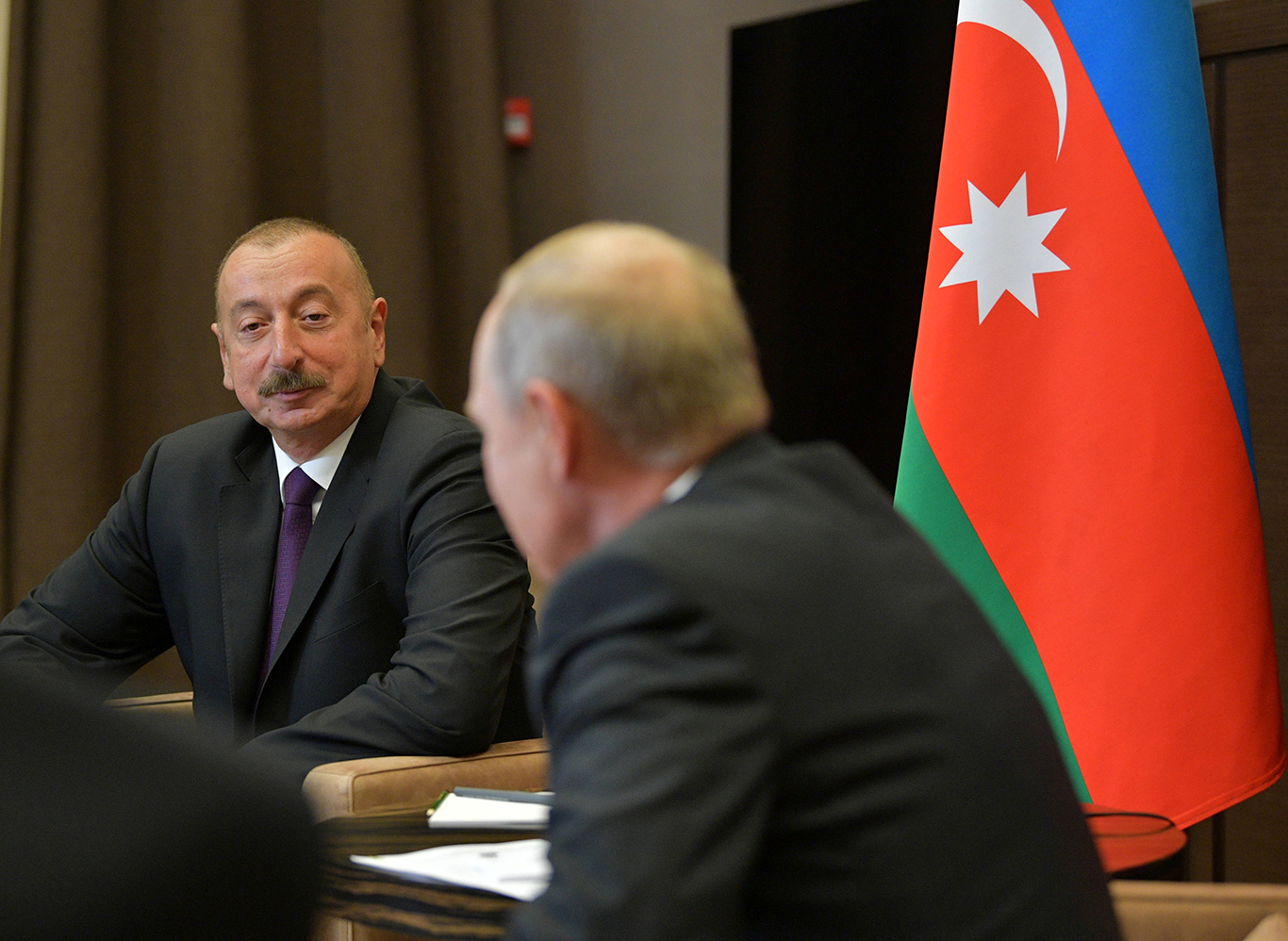

The Fifth Caspian Summit in Aktau, Kazakhstan, which resulted in the adoption of a convention on the legal status of the Caspian Sea, and German Chancellor Angela Merkel’s visit to the Caucasus, including Baku, had hardly ended before the public’s attention was caught by a meeting between the presidents of Azerbaijan and Russia in Sochi on 1 September. At the meeting, Vladimir Putin stressed the strategic nature of the relationship between the two countries and thanked Ilham Aliyev for the the latter’s visit. For his part, Aliyev invited Putin to visit Azerbaijan at his convenience, while Russian TV channels aired warm reports about the presidents’ meeting that suggested that the heads of state were pleased with its results.

A joint statement was signed “On priorities in economic cooperation between Russia and Azerbaijan”, which envisages an increase in trade and investment, development of transportation infrastructure, humanitarian cooperation, and development of culture and tourism ties. More than a dozen agreements were also signed to expand cooperation in different fields. In particular, Rosneft and the State Oil Company of Azerbaijan agreed on a joint exploration of the oil and gas field Goshadash in the Azerbaijani section of the Caspian Sea, and GAZ Group and Azermash agreed to start assembling GAZ vehicles in Azerbaijan. In addition, Gazprombank intends to invest about $750 million in the development of the Sumgayit chemical industrial park. Attention was also paid to one of the most promising projects – the North-South transportation corridor – which will link the Baltic countries and India via Iran.

Experts believe, however, that many issues raised at the meeting – which observers call a “surprise” meeting that was announced a mere eight hours before it started – remained in the shadows. Azerbaijani political circles believe that Azerbaijan’s prospects for joining the Eurasian Economic Union and even the CSTO (Collective Security Treaty Organization) were also discussed. In any case, Azerbaijani media widely discussed these issues ahead of the meeting, even though Azerbaijan’s accession to those organizations does not seem very likely because of a whole host of factors and, primarily, the Karabakh conflict which certainly was discussed, as were regional security problems overall.

The overwhelming majority of Azerbaijani analysts, politicians and journalists came out against Baku’s joining the CSTO, which is no surprise. How is it possible, considering that Armenia, whose conflict with Azerbaijan goes back decades, is already a member? Most analysts are unanimous that the rumors about the CSTO – at least at this time – are simply a way of putting pressure on Yerevan, especially considering the fact that there are voices in the new leadership who would like to leave the organization. We should note right away that Russia has always tried to keep its bilateral relations with Azerbaijan separate from the issue of Nagorno-Karabakh. On the contrary, when conducting its foreign policy, Baku views its relations with other countries, including Russia, through the prism of the conflict. One can assume that the meeting also touched on the issue of the shutdown in Russia of the All-Russian Azeri Congress, which caused Baku’s discontent.

Moscow appears to believe that the situation in the South Caucasus may change for the worse, and not only because of Karabakh. The new government in Armenia does not seem to have made up its mind yet about its foreign policy goals. This is a situation that Moscow cannot like. There are voices in Moscow that say, as a hint to Yerevan, that the Kremlin may start looking for new ways of supporting stability in the region and the balance of weapons that the conflicting sides have. Translated from diplomatic language, this indicates the possibility of the formation of a new strategy in Russian-Azerbaijani relations if the Kremlin finds, as the Russian press puts it, that “an Armenian Maidan with American ears” runs counter to Russia’s interests. It was for that reason that a $5 billion bilateral military contract between Azerbaijan and Russia was announced at the press conference. In addition, two days after Sochi, Ilham Aliyev attended a meeting of the Cooperation Council of Turkic-Speaking States in the town of Cholpon-Ata in Kyrgyzstan, at which he expressed hope for support from Turkic-speaking states in the Karabakh issue.

However, a summit of Turkish-speaking states is not the kind of a meeting at which agreements are concluded, major projects planned, or military blocs established against third countries. Especially as Turkey, a participant in the summit, is a NATO country, while Kazakhstan and Kyrgyzstan, which also participated in the summit, are members of the CSTO. However, there is no doubt that Yerevan will heed this news, especially as TurAz Falcon-2018 joint military drill started at an airbase in the Turkish city of Konya on the day the summit was held. Incidentally, it was decided to hold the next summit of the Cooperation Council of Turkic-Speaking States in Baku in 2019.

There was no mention of it, but it is reasonable to assume that an initiative put forward by Turkey – Azerbaijan’s closest ally – was also discussed at the meeting. Turkey suggested abandoning the dollar in transactions in interstate trade. Ankara says that its national currency, which has lost more than 40 per cent of its value since the beginning of this year, has depreciated because of an increase in US import customs duties for Turkish steel from 25% to 50% and for aluminum from 10% to 20%. Turkish President Recep Tayyip Erdogan had said earlier that talks between Turkey and Russia on using national currencies in bilateral trade were already under way and that in this way he intended to put an end to the dollar’s monopoly in international transactions.

The very fact that the Russian and Azerbaijani leaders met, which apparently was not planned in advance, suggests that Moscow has started to pay increased attention to problems of security and stability in the Caucasus and will strive in the very near future to prevent the spread of Middle Eastern conflicts to the South Caucasus. In this context, Moscow’s aspiration to strengthen relations with Baku in various fields and intensify political contacts looks logical, especially considering the fact that ISIS, which is active in the Middle East, can, if not completely then at least partially, “overflow” from Syria to the South Caucasus, especially to traditionally Muslim Azerbaijan. This would threaten Russia’s national security as well as projects like the North-South transportation corridor and even the development and transportation of Caspian hydrocarbons. Certainly, one could draw different pipeline routes on the map but that will not repeal the iron rule that no one will invest in a region where an armed conflict is brewing or already underway.

The main problem is how to normalize relations between Azerbaijan and Armenia, which for the time being remains the Kremlin’s strategic ally because its security depends on Russia. Besides the conflict with Azerbaijan, Armenia has strained relations with Turkey, which is an ally of Azerbaijan, and has problems in its relations with Western countries. Some experts believe – prematurely, perhaps – that all this may make Azerbaijan Russia’s main partner in the Caucasus. However, whether Russian diplomacy will manage to change the geopolitical landscape of the entire region to is a question that cannot be answered for the time being.

In any case, one can expect Russia to make some attempts. One indication is Vladimir Putin’s upcoming visit to Azerbaijan, at Ilham Aliyev’s invitation, at the end of September. Apart from that, the Russian president will visit Tajikistan on 27-28 September to take part in a meeting of the leaders of CIS member states, and in October a visit to Uzbekistan is scheduled. It is clear that all these visits have not been planned merely to enjoy some southern hospitality.