At the beginning of April, escalation on the Line of Contact (LoC) separating Armenian and Azerbaijani forces in and around the disputed territory of Nagorno Karabakh marked the worst flare up in fighting since the 1994 ceasefire was signed. With precise figures hard to come by, at least 100 soldiers died on both sides and several civilians were killed in what has become known in some circles as the “Four Day War.”

Certainly, it has long been true that the Nagorno Karabakh conflict can no longer be considered a ‘frozen conflict.’ Some might even have doubts about the continued use of the term ‘ceasefire.’

Naturally, patriotic and nationalist emotions were stirred on both sides, in part fueled not only by pent-up frustrations, but also by a steady stream of misinformation and propaganda eagerly shared on Facebook and Twitter. Tensions were even noticeable in neighboring Georgia where the country’s ethnic Armenian and Azeri populations receive their news mainly from media in Armenia and Azerbaijan proper.

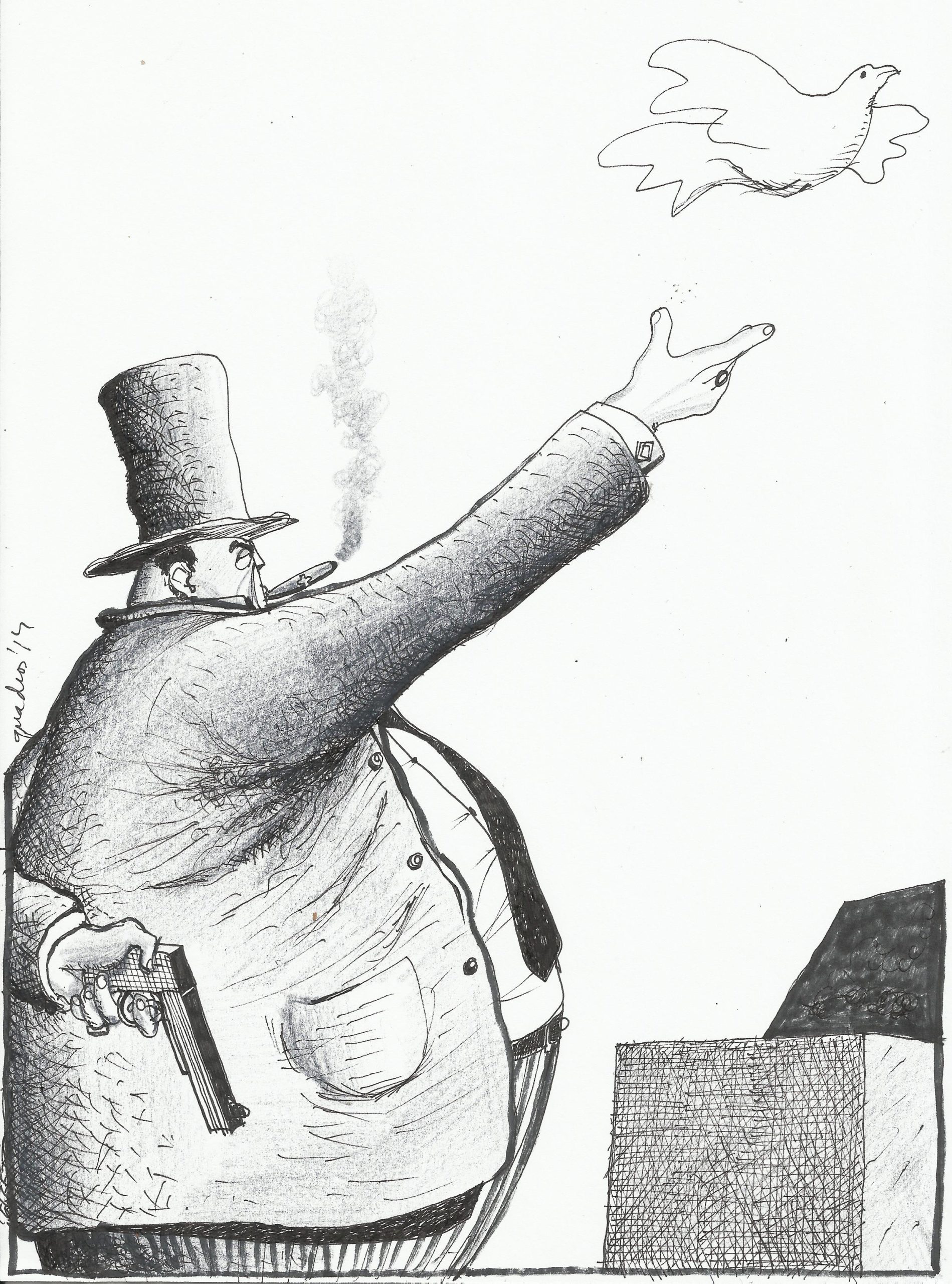

What was unexpected, however, was the reaction of past and present peace – building projects and organizations: “Dear friends, please clearly identify your own values and try to stick to them,” wrote one Azerbaijani activist on Facebook in response. Some Armenians noted the same tendency there as well. Those supported by international donors in the past now became willing combatants online and

some even expressed a desire to join in the fight.

Putting aside concern for ‘normal citizens’, it was the heads and employees of several NGOs long thought to be progressive and interested in working towards peace that instead turned out to be fervent supporters of military action or possible war. Writing last month in the Washington Post, David Ignatius even referred to one of these activists as a ‘former peace activist.’

Armenia and Azerbaijan again demonstrated not just how far apart they are on many issues, but how similar they can be in terms of mentality and attitudes. The pro-government camps, of course, were never known for being ‘peaceful,’ and opposition figures have always been accused of working for the ‘interests’ of the ‘enemy.’ Some of the latter have even expressed solidarity, or taken part in conferences and seminars in third countries such as Georgia.

Yet, during the recent escalation, those ‘liberals,’ especially among youth leaders, accused the other side of being far behind in terms of progress and of displaying barbarous behavior. And in doing so, each side proved the other correct. Perhaps the masses, and especially the youth, were expecting change from the wrong people.

In Armenia, the ‘progressive’ element in society pointed to anti-government displays of protest such as ‘Electric Yerevan’ as the start of a movement that could now be built upon by the recent bloodletting in Karabakh. Talk among those previously fighting for democracy was to fight corruption and the oligarchic system in Armenia in order to strengthen the country’s military prowess against the ‘enemy.’

And in Azerbaijan, it was business as usual. Why?

Because ‘conscription’ for the regime had already began with Baku European Games, when some activists volunteered for the games despite criticism from the opposition. This wave of ‘changing sides’ was accelerated by protests in Nardaran. While pro-government media outlets like ‘Femida.az’ or ‘AzVision.az’ fulfilled their regular mission of propaganda during the crackdown on the town, it was not expected for the opposition to back their rivals.

However, mass hysteria caused opposition to see the protests as a real threat of a

coup-d’etat (as if there could be one). As Azerbaijanis say, the April clash was ‘the last drop’.

The “Four Day War” was also a testament to Azerbaijan’s oppression of and restriction on the media. While on the

Armenian side there were many foreign journalists reporting, including the BBC, Azerbaijan’s visa policy did not help international journalists, many of whom simply could not enter. Local journalists were not active, and even though they were in Armenia, both contributed to a surge of misinformation and propaganda to agitate and beat the war drum among the masses.

What happened to the tens or even hundreds millions of dollars and euros spent on peace-building initiatives since the 1994 ceasefire?

Why were many of those who had been part of such projects so quick to forget the relationships they assured donors had been nurtured across the border and front line? And why, despite some €5.8 million being spent on the EU’s European Partnership for the Peaceful Settlement of the Conflict over Nagorno Karabakh (EPNK) from 2012 to 2015, did only a handful of its participants not remain silent and reject or oppose any inclination to become online combatants?

For too long, projects such as EPNK – for those that actually know about it – have been plagued by a feeling that the ‘usual suspects’ operate in ‘closed circles,’ always using the excuse of ‘security concerns’ to justify doing nothing with projects voluntarily bid on and funded by international donors. Ironically, despite the greater risks, they haven’t felt as insecure in criticizing their respective governments on corruption and human rights abuses.

Arif and Leyla Yunus were not arrested for their peace-building work with their Armenian counterparts. That was only an excuse. They were instead prosecuted for their outspoken criticism of the Aliyev Regime.

And in Armenia, with a handful of exceptions, most declaring their intent to work toward peace approach have done so in almost half-hearted or even disingenuous way. “We’ll make it clear to the Azeris that we want Nakhichevan,” said the head of one NGO during a closed meeting in Yerevan regarding a project funded in 2010 by the British Embassy’s Conflict Pool.

What was once said in private became public during the recent escalation.

Countless media strengthening and conflict-sensitive journalism projects have likewise proven ineffective or even pointless. As part of EPNK and other donor-funded projects, such trainings have even been conducted by those from abroad unaware of the specifics and problems of the Nagorno Karabakh or by those who have now revealed their true nature. The use of social media by those involved in peace-building activities has been amateurish at best.

For many of us, the problems have long been known. So what about solutions?

- To begin with, international donors should set strict policies and rules when dispensing grants for projects from Armenia and Azerbaijan. The experience last month, however, shows that interviews and personal relationships are not enough to assess how genuine grantees are. Responses to the recent escalation should now be considered a criteria too.

- “Media Monitoring” should be considered a perpetual and continuous need in order to fight against propaganda disinformation. This project should be implemented by Armenians and Azerbaijanis in tandem, but in conjunction with neutral editors, possibly including those from Georgia.

- While existing media projects do exist, few participants communicate or cooperate with their counterparts across the border. Even fewer use social media adequately or at all despite its role and use as a main channel of propaganda and disinformation during the recent escalation.

- Peace-building initiatives should be coordinated from Tbilisi and not from London, Washington DC, or elsewhere. Managing such projects outside of the conflict zone has proven ineffective and costly in terms of salaries, per diems, and hotel costs while also preventing genuine and lasting relationships from being formed with grantees.

- Peace-building projects and initiatives should be more inclusive. None of those currently operating attempt to widen their pool of participants or beneficiaries, instead preferring to remain in their own insular social and political circles. The reality of ‘usual suspects’ and ‘closed circles’ must end.

- Genuine amplifiers on social media, especially individual users on Facebook and Twitter, should be included in such projects. For now, those that do have the networks and ability to reach many more people than NGOs – who continue to display an inability to harness the power of the medium properly even if they wanted to – remain excluded.

- Support for grassroots activities should take precedent over large, bloated, and ineffective projects usually awarded to the same grantees that have failed to make any noticeable impact on society at large. Effective ideas are more likely to come from these circles rather than a civil society that has largely become part of the establishment.

The recent escalation on the Line of Contact (LoC) highlighted the deficiencies of virtually all peace-building projects to date, and especially in terms of their inability to genuinely work towards peace or deliver their message to a wider segment in both societies. In order to avoid another such escalation, prevent a possible war, and contribute to an eventual peace, that must change.

And sooner, rather than later.

This article reflects the view of the authors and as such may not coincide with that of Meydan TV.

—

Cavid Aga is a column writer for BBC Azerbaijani and translator of “Arthur Schopenhauer – Eristic Dialectics” into Azerbaijani language which was published in 2015. He can be followed on Twitter at @cavidaga.

Onnik James Krikorian is a journalist and consultant from the UK who has covered the Nagorno Karabakh conflict since first visiting for The Independent newspaper in 1994. He has been a consultant and trainer on numerous cross-border conflict-related projects. He can be followed on Twitter at @onewmphoto.